Rina BANERJEE (1963)

Plasticienne indienne.

Rina Banerjee émigre très jeune avec sa famille à Londres, puis aux États-Unis, où elle obtient son diplôme en peinture et gravure à Yale en 1995. Marquée par cette oscillation entre deux cultures, son œuvre, à la lecture complexe, s’intéresse très tôt au thème de la migration au travers d’une réflexion sur la mémoire, l’expérience, la mobilité des communautés, le local et le global. Elle questionne globalement la notion d’identité et se penche aussi sur la féminité, la sororité. Membre de la diaspora, elle en évoque la nature délicate, dans une société qui se veut multiculturelle. Plus largement, elle aborde la problématique du rapport à l’autre – dans la progression du sida, par exemple – ou bien à l’étranger, qu’elle représente souvent sous forme d’insecte. Elle brouille les pistes lorsqu’il s’agit d’évoquer l’ethnicité ou exotisme supposé, comme en témoigne sa réflexion sur la symbolique des vêtements, à la fin des années 1990.

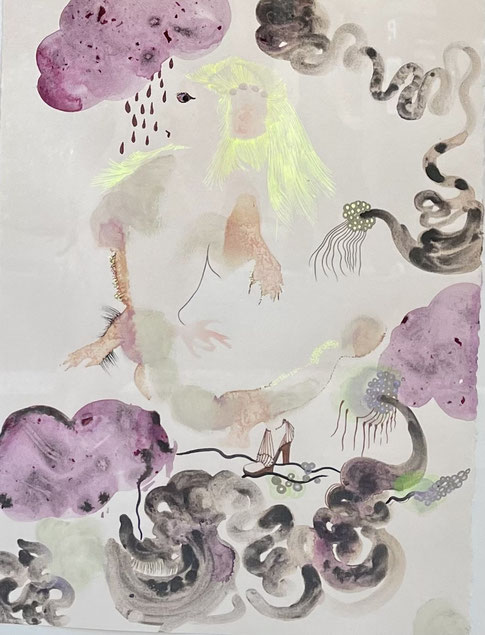

Ses œuvres sont toujours très conceptuelles, qu’il s’agisse d’installations, comme sa série sur le Taj Mahal, Take Me, Take Me, Take Me… to the Palace of Love (« Emmène-moi, emmène moi, emmène-moi… au palais de l’amour », 2003), ou bien d’œuvres sur papier, parfois « faites main », telles que Seasoned by hurricanes, sweet water and salty air thisunearthly place made into home for “she” who bit twice the fruit of its displeasure (« Asséché par les ouragans, l’eau douce et l’air salé ce lieu surnaturel transformé en maison pour “elle” qui mordit deux fois le fruit de son mécontentement », 2007), où se mélangent encre, acrylique, aquarelle, voire perles de verre. Les titres, dont les fautes et les syntaxes longues lui permettent de jouer avec la langue et les sons, tout comme elle joue avec les postures, les couleurs, chaudes ou froides, les matériaux, organiques ou industriels, les effets de transparence et l’espace, en multipliant les motifs floraux et végétaux pour combler les vides.

Entre le sol et le ciel se créent des juxtapositions, des liens, des tensions, sans qu’aucun élément soit privilégié par rapport aux autres. À partir de figures énigmatiques ou universelles, comme celles du serpent ou de l’araignée, R. Banerjee ouvre un vaste champ de possibles et libère les objets de tout déterminisme ; inspirant fascination ou répulsion, ils deviennent, comme par magie, ce qu’ils ne sont pas a priori, dans des œuvres à la fois noires et séduisantes.

Indian visual artist.

Rina Banerjee emigrated at a very young age with her family to London, then to the United States, where she obtained her degree in painting and engraving at Yale in 1995. Marked by this oscillation between two cultures, her work, with its complex reading, focuses on very early on the theme of migration through a reflection on memory, experience, the mobility of communities, the local and the global. She generally questions the notion of identity and also looks at femininity and sorority.

A member of the diaspora, she evokes its delicate nature, in a society that aims to be multicultural. More broadly, she addresses the issue of relationships with others – in the progression of AIDS, for example – or with strangers, whom she often represents in the form of an insect. She blurs the lines when it comes to evoking ethnicity or supposed exoticism, as evidenced by her reflection on the symbolism of clothing at the end of the 1990s.

His works are always very conceptual, whether they are installations, like his series on the Taj Mahal, Take Me, Take Me, Take Me... to the Palace of Love ("Take me, take me, take me- me… at the palace of love”, 2003), or works on paper, sometimes “handmade”, such as Seasoned by hurricanes, sweet water and salty air thisunearthly place made into home for “she” who bit twice the fruit of its displeasure (“Dried up by hurricanes, fresh water and salt air this supernatural place transformed into a house for “she” who twice bit the fruit of her displeasure”, 2007), where ink, acrylic, watercolor, even glass beads. The titles, whose mistakes and long syntax allow her to play with language and sounds, just as she plays with postures, colors, warm or cold, materials, organic or industrial, effects of transparency and space, by multiplying floral and plant motifs to fill the gaps.

Between the ground and the sky juxtapositions, links, tensions are created, without any element being privileged over the others. Using enigmatic or universal figures, such as those of the snake or the spider, R. Banerjee opens a vast field of possibilities and frees objects from all determinism; inspiring fascination or repulsion, they become, as if by magic, what they are not a priori, in works that are both dark and seductive.